Santa Freud Friend

Rebecca Johnson

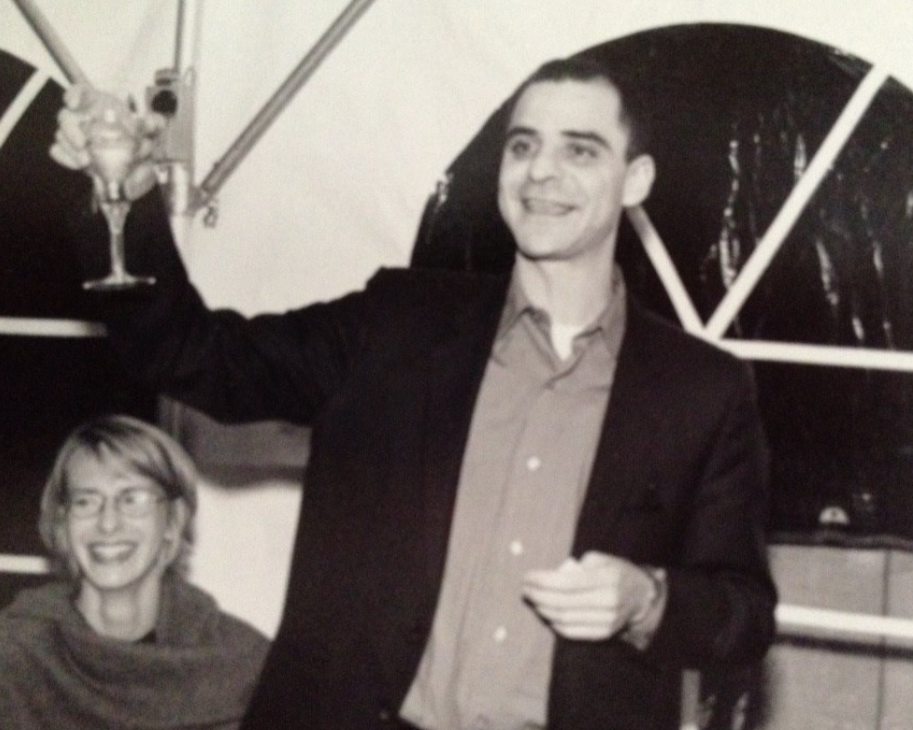

The writer, David Rakoff, giving a toast at author’s wedding

Word Count 2009

I became friends with the wildly talented writer, David Rakoff, at college in the 1980’s. At the time, he wasn’t famous, of course. All that came later. He was always funny but his humour was derived from being alienated by all the things that most of us take for granted–country of origin (Canada), sexuality (gay) and the blustery charm of his adopted country (America). He delighted in being the center of attention, but an afternoon with David was never relaxing. His fertile imagination was always in overdrive, looking for the pithy comment, the world weary bon mot that would make his audience guffaw in delight. I loved him and there was a period in my life when we literally spoke every afternoon on the phone, but I often saw the melancholy behind his facade.

After college, he became friends with another wildly talented gay writer named David Sedaris who is now–as we all know– a global phenomenon. Sedaris began his march to stardom with “Santa Land” on NPR, a charming essay about his stint as an elf in the Macy’s Christmas tableaux. Management at the luxe department store Barneys must have taken note and decided that they, too, wanted to hire a living writer to enliven their department store windows during the holiday season. Enter David Rakoff as Sigmund Freud.

When I heard that David was going to be sitting in a department store window pretending to be the famous psychoanalyst, I was shocked. Though he fancied himself an actor, those of who knew him well, knew that was a non-starter. He could charm the pants off a casting director but he was way too cerebral and self conscious to ever lose himself in a role. It took all the concentration he had to play the role of David Rakoff. I still remember how upset he was when he was fired from the role of the flaming wedding planner in The First Wives Club, a role that eventually went to Bronson Pinchot. (When the movie came out, he would derisively refer to the character as “Fudgie McFudge Packer.”)

At the time of the Freud window spectacle, I was working in the old Conde Nast building at 45th and Madison. I liked to go there on weekends to write because the desk in my windowed office was more comfortable than my desk at home and I kind of adored the view of the Roosevelt hotel and the whole Mad Man vibe of that corner of the world (it helped that Brooks Brothers, then in its heyday, was in our lobby.) I decided to take a walk and visit David in his window.

When I got to the corner of 60th and Madison, I could see a crowd gathered in front of the windows, which had become a New York phenomenon, thanks to an elfin Englishman named Simon Doonan. I muscled my way into the throng and found myself gazing at my old friend reading a book in his glass cage. I didn’t really know what to do. Knock on the glass to get his attention? Hey, David, it’s me! Do you get a break soon? Stick around and hope he looked up to recognize me? He looked stern and kind of annoyed, deeply absorbed in the reading of a book.

I didn’t much care for the attitude of the crowd, who seemed to regard him as a baboon at the zoo. It seemed like a violation of the unspoken rules of human dignity–if people are going to look at you, you ought to be able to look back at them. Years later, when I strolled the red light district of Amsterdam, I felt the same way about the prostitutes sitting in the window. Eventually, I turned around and went back to my office, never telling him that I had been there. Nevertheless, I had begun to discern an inequality in our relationship that afternoon which only deepened over the years. David was a more talented writer than I was and, just as important, he was willing to do whatever it took to become the star that he would eventually become.

The last time I saw David, we had lunch at a diner near Gramercy Park. He seemed out of sorts and complained about a pain in his shoulder, but told me he was seeing a doctor later that week and it was probably just a pinched nerve. It turned out to be a rare soft tissue sarcoma in his shoulder that would kill him, two years later, at the age of 47.

Below is a transcript of his essay, which can be heard here. I can’t listen without weeping.

https://www.thisamericanlife.org/47/christmas-and-commerce.

I am the ghost of Christmas subconscious. I am the anti-Santa. I am Christmas Freud. People tell me what they wish for. I tell them the ways their wishes are unhealthy or wished for in error. My impersonation merely involves me sitting in a chair either writing or reading The Times or The Interpretation of Dreams every Saturday and Sunday until Christmas.

I sit in a mock study facing Madison Avenue at 61st Street. My study has the requisite chair and couch. It's also equipped with a motorized track on which a video camera-wielding baby carriage travels back and forth, a slide projector, a large revolving black and white spiral, two hanging torsos, and about 10 video monitors that play Freud-related text and images.

When I sit down in the chair for the first time, I'm suddenly horrified at the humiliation of this. And I have no idea how I'm going to get through four weekends sitting here on display. And this role raises unprecedented performance questions for me. For starters, should I act as though I had no idea there were people outside my window? I opt for covering my embarrassment with a kind of Olympian humorlessness. If they want twinkles, that's Santa's department.

I am gnawed at by two fears. One, that I'm being upstaged by Linda Evans' wig in the blonds window. And two, that a car will suddenly lose control, come barreling through my window, and kill me, an ignoble end to be sure, a life given in the service of retail.

Sometimes, for no clear reason, entire crowds make the collective decision not to breach a respectful six foot distance from the window. Other times, they crowd in, attempting to read what I'm writing over my shoulder. I thank God for my illegible handwriting.

Easily half the people have no idea who I'm supposed to be. They wave, as if Freud was Garfield the cat. Others snap photos. The waves are the kind of tiny juvenile hand crunches one gives to something either impossibly young and tiny or adorably fluffy. "Oh, look. It's Freud. Isn't he just the cutest thing you ever saw? Aw, I just want to bundle him up and take him home."

There are also the folks who are more concerned with whether or not I'm real. This I find particularly laughable, since where on Earth would they make mannequins that look so Jewish? My friend David came up yesterday, and was writing down what people were saying outside. "He really looks like him, only younger." "Hey, that's a real guy." "He just turned the page. Is he allowed to do that?" "Who is that, Professor Higgins?"

If psychoanalysis was late 19th century secular Judaism's way of finding spiritual meaning in a post-religious world and retail is the late 20th century's way of finding spiritual meaning in a post-religious world, what does it mean that I'm impersonating the father of psychoanalysis in a store window to commemorate a religious holiday? In the window, I fantasize about starting an entire Christmas Freud movement. Christmas Freuds everywhere, providing grownups and children alike with the greatest gift of all, insight.

In department stores across America, people leave display window couches snifflingly and meaningfully whispering, "Thank you, Christmas Freud," shaking his hand fervently, their holiday angst, if not dispelled, at least brought into starker relief. Christmas Freud on the cover of Cigar Aficionado magazine. Christmas Freud on Friends. People grumbling that-- here it is, not even Thanksgiving, and already stores are running ads with Christmas Freud's face asking the question, "What do women want for Christmas?"

If it caught on, all the stores would have to compete. Bergdorf Goodman would leap into action with a C. G. Jung window, a near-perfect simulation of a bear cave. While the Melanie Klein window at Niketown would have them lined up six deep. And neighborhood groups would object to the saliva and constant bell ringing in the Baby Gap's B. F. Skinner window.

There's an unspeakably handsome man outside the window right now, writing something down. I hope it's his phone number. How do I indicate to the woman in the fur coat, in benevolent Christmas Freud fashion, of course, to get the hell out of the way? Then again, how does one cruise someone through a department store window? Should I press my own phone number up against the glass, like some polar bear in the zoo holding up a sign reading, "Help! I'm being held prisoner"?

One day, I come up to the store for a photo op for a news story about the holiday windows of New York. It is my 32nd birthday. I am paired with a little girl named Sasha. It's her birthday, as well. She is turning 10. She is strikingly beautiful and appears in the upcoming Howard Stern movie. She's to be my patient for the photographers.

In true psychoanalytic fashion, I make her lie down and face away from me. I explain to her a little bit about Freud, and we play a word association game. I say, "Center." She responds, "Of attention." I ask her her dreams and aspirations for this, the coming 11th year of her life. "To make another feature and to have my role on One Life to Live continue." She sells every word she says to me, smiling with both sets of teeth, her gem-like eyes glittering. She might as well be saying, "crunchy" the entire time. But she is charming. I experience extreme countertransference.

I read a bit from The Interpretation of Dreams to her. "Is this boring?" I ask. "Oh, no. It's relaxing. I've been working since 5 o'clock this morning. Keep going." Even though her eyes are closed, she senses the light from the news cameras on her. She curls towards it like a plant and clutches her dolly in a startlingly un-childlike manner. The glass of the window fairly fogs up.

My photo op with Sasha leads me to the decision to start seeing patients throughout my stint. I'm simply not man enough to sit exposed in a window doing nothing. It's too humiliating and too boring. My patients are all people I know. Perhaps it's because the couch faces away from both the street and myself that the sessions are surprisingly intimate. But it's more than that. The window is, weirdly enough, very cozy, more like a children's hideaway than a fish bowl. Patients seemed to relax immediately upon lying down.

T. begins the session laughing at the artifice, and ends it actually crying on the sofa. Christmas Freud is prepared and hands him a handkerchief. J. has near-crippling tendinitis and wears huge, padded orthopedic boots. The people watching think it's a fashion statement. She wears a dress from Loehmann's, but I treat her anyway. G., a journalist likes to talk with children and write about them. Perhaps that's why his shirt is irregularly buttoned.

I'm told that a woman outside the window wondered aloud if I was an actual therapist. I suppose there must be one in this town who would jeopardize his or her credibility in that way. I've scheduled our next session for the window at Barney's. I hope that's OK. Huh, you seem really resistant. Do you want to talk about that?

A journalist is doing a story on the windows for The Times. He asks me if this is a dream come true. Well, it is a dream. "It's logical," I reply. "One of my parents is a psychiatrist. And the other one is a department store window." He doesn't laugh at my joke, but it's half true. One of my parents is a psychiatrist. The other is an MD who also does psychotherapy.

I've been in therapy myself, for seven years. The difference between seeing a shrink and being a shrink is not only less pronounced than I imagined it might be, it feels intoxicating. When my own therapist of seven years says, "I have a fantasy of coming by the window and being treated by you," I think, "Of course you do." I feel finally and blissfully victorious.

My father tells me a dream he had in which I have essentially analyzed and exposed him. It's the only indication I've gotten from him so far that he is anything other than amused by what is, basically, a mockery of what he does. In a certain sense, I'm not just aping my father and my mother but also, in a way, their father, the man who spawned their profession.

And when I sit there, a patient on my couch, pipe in my mouth, listening, it feels so perfect. Like any psychiatrist's kid, I know enough from growing up and from my own years on the couch to ask open-ended questions, to let the silences play themselves out or not, to say gently, "Our time is up," after 45 minutes. The charade feels real, the conclusion of an equation years in the making.

Even the media coverage for this escapade is extensive and strange. People from newspapers and television are asking me deep questions about the holiday, the nature of alienation at this time of year, things like that, as though I actually was Freud. It's disconcerting because, with very little effort, I could be drunk with the power. But it also points out the O. Henry "Gift of the Magi" quality of it all. The media is so desperate for any departure from the usual holiday stories they have to turn out, they come flocking. And yet, the public doesn't really even want to read about the holiday in the first place. It's like trying to jazz up a meal nobody wants to eat anyway.

I get a call from the store that Allen Ginsberg might be in the beats window on Sunday. And if he wants to, would I speak to him? "I have no sway over Mr. Ginsberg. But if he has something he would like to talk about, I'm certainly available," I tell them. Not entirely true. I'm pretty well booked.

The whole Allen Ginsberg thing depresses me a bit. Then again, if he can see it as a cosmic joke, why can't I? I feel indignant and very territorial. Impostors only. No real ones in the window. Anyway, it's moot. He doesn't show up.

There is a street fair outside that teams to have brought a decidedly scarier type of spectator. They are like the crowd at a carnival, and I'm the dog-faced boy. A grown woman sticks her tongue out at me. Later, during a session, a man in his 50s presses his nose up against the window, getting grease on the glass, presses his ears up to hear, and screams things at me I cannot hear.

When I leave after each stint, I put up a little glass sign that reads, "Freud will be back soon." It's like a warning, the post-modern version of "Christ is coming. Repent." Freud will be back soon, whether you like it or not. Freud will be back soon. Stop deceiving yourselves.

In the affluent downtown neighborhood in Toronto in which I was raised, someone had spraypainted on a wall "Mao lives," to which someone else had added, "here?" My window is a haven in Midtown. I can sit there unmindful of the crush in the aisles of the store, the hour badly spent over gifts thoughtlessly and desperately bought. As I sit there I hear the songs that play for the display one window over, the blonds of the 20th century. Doris Day singing "Once I Had a Secret Love." Mae West singing "My Old Flame." Marlene Dietrich singing "Falling in Love Again. As I listen, I feel that they're really referring to my window, to Freud. Every time they come up on the repeating tape, I find them almost unbearably poignant, with all their talk of clandestine love, erotic fixation, and painfully hidden romantic agenda.

But they might also just as easily be referring to this time of year, with the aching sadness and loneliness that seems to imbue everything. Where is that perfect object, that old flame, that secret love that eludes us? Unfindable, unpurchaseable.

This is my final weekend as Christmas Freud, and I'm starting to feel bereft in anticipation of having to take down my shingle. I started off as a monkey on display and have wound up

uncomfortably caught between joking and deadly serious, a persona that seems laughable at times, fated for me at others. I know this will pass, but for now I want nothing more than to continue to sit in my chair, someone on the couch, and to ask them, with real concern, "So tell me, how's everything?"

Rebecca is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in various publications including (alphabetically) Elle, Mademoiselle, The New Yorker, The New York Times, The NYT Magazine, Salon, Vogue (contributing editor 1999-2020). Johnson is the author of the novel And Sometimes Why. She lives in Brooklyn, New York with her husband and two children.