MRI

Lisa M. Orange

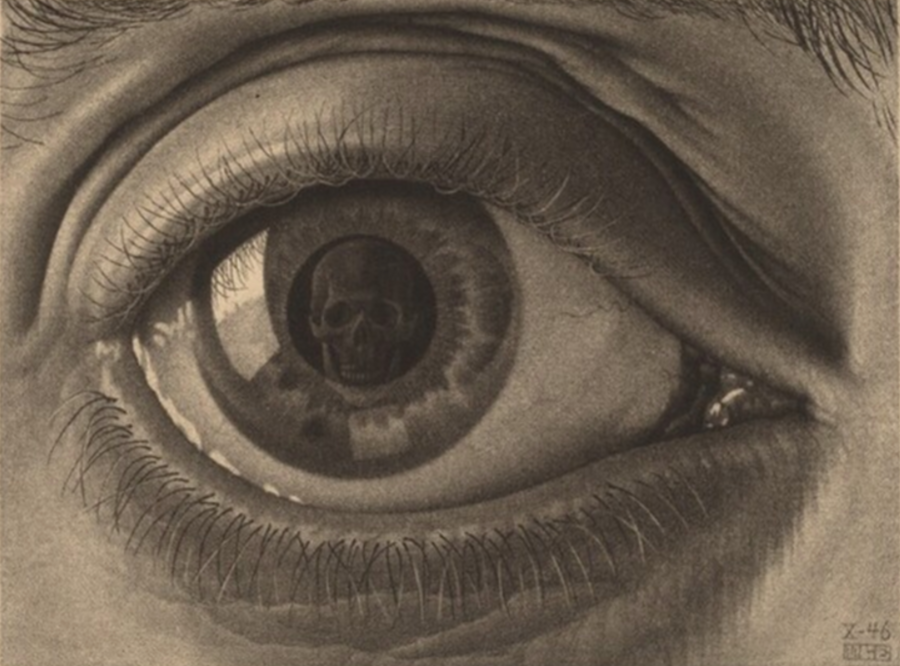

Escher, M.C. 1946

Word Count 1068

My vision in one eye has grown cloudy at the center, as if I’m looking through a dirty window. An ophthalmologist suggests I have optic neuritis, an inflammation of the optic nerve. The term is familiar, but I can’t quite place it, so I pull out my cell phone. “...(O)ften associated with multiple sclerosis, and can be an early sign of the disease.”

Shock races through my body, as the puzzle pieces fall together. My father had been diagnosed with MS in his late 40s, roughly the same age that I am now. He too had gone to his ophthalmologist with early symptoms and learned that he had optic neuritis.

The doctor schedules a brain scan to look for the tell-tale lesions of MS: luminous white dots in the grayscale images generated by an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scanner.

I’m not claustrophobic, but I worry about how I’ll tolerate the tight confines of the MRI during the noisy 90-minute procedure. I find a website whimsically called MRI Jukebox with samples of all the sounds. I decide to keep my eyes closed and invent stories, telling myself tales to accompany the barrage of hammering, drilling, droning sounds.

The scanner hums and clicks at the center of the chilly exam room. It looks like a giant donut, with a table through the hole in the middle. I am padded with earplugs, headphones, a warm blanket, and cushions stabilizing my head. I feel calm and almost cozy as the scanner’s flatbed glides with me into the narrow tunnel. A fan wafts a gentle stream of air across my closed eyes.

The machine’s vibrant drone reminds me of a motorboat. I remember cruising with my family on Deep Creek Lake, a Maryland park where we used to vacation. I summon as many details as I can: the wooded shoreline, verdant green hills, children playing on the beach, sunlight dappling the water, the boat bounding across the waves.

The scene grows increasingly vivid, as if I’ve slipped inside a movie. I stand in the stern and watch my two sons, little boys again, bouncing in an inner tube pulled behind the boat. They skim along the surface, waving wildly, shrieking with laughter. My husband is at the helm. He smiles at me, and his loving gaze is so real that actual tears slip from beneath my eyelids.

Suddenly the scanner goes silent. My mental movie screen fades to black.

Then comes a flurry of clacking, hooting and honking. Fantastic musical instruments appear in my mind, brass and timpani that Dr. Seuss might draw.

In this new vision, I’m standing in the sanctuary of my church, chairs pushed aside and crazy contraptions all around me. Friends and family members step out of the shadows to form a circle with me at the center. They make exuberant music, tapping and shaking and blowing into their instruments as I dance up to each one in turn. We play and stomp and laugh and circle, drumming the demons away.

The machine falls quiet again and the friendly faces vanish.

The technician speaks gently in my headphones. “You’re doing great. This is the last part. Just a few more minutes.”

Now the machine thrums like a powerful sports car. I see myself cruising an exquisitely beautiful stretch of California Route 1, hugging the cliffs of Big Sur, the radiant blue Pacific below. I am the passenger in a cherry-red convertible, a vintage Triumph Spitfire. I feel a rush of cool breeze, scented with Monterey pine.

My father is at the wheel, expertly shifting gears, a wide grin on his face. This is the father of my childhood, the man who saved his vacation days to spend a summer driving his family across the country to visit a dozen national parks. The amateur race-car driver. The responsible motorcycle rider. The roller coaster enthusiast. The NASA engineer who wanted to be an astronaut.

The scene changes to somewhere in the heartland. We’re surrounded by golden grasses and wide blue sky. The empty road stretches before us like an endless carpet runner. Dad revs the motorcycle that he hasn’t touched in years. I swing a leg over, wrap my arms around him and press my cheek against his back, leaning with him as he carves a turn.

This reverie is not about the girl that I was when Dad and I last rode together. Nor am I a middle-aged woman with blurred vision. On this ride, he is ageless, and I am too.

Too soon, the engine noise fades. I stand in the road as the motorcycle leaves me behind.

I feel the table roll smoothly out of the scanner, and I open my eyes to the glare of fluorescent lights. Ninety minutes have passed, the way time unfurls in a dream, weighted with emotion yet free of limitations.

A few days later, the neurologist and I review the results of the MRI. I imagine that the ghostly black-and-white images are what you might see if you took off the top of my head and gazed down from above, diving into my brain, layer after layer.

The doctor identifies some of the white shadows. “This here, this is normal brain structure,” he explains.

“This, over here… This is not.”

He’s pointing to an intensely white dot, the size of a pencil eraser on the computer screen. The brightness means that this is a new lesion; older lesions are pale.

I should be horrified by this undeniable evidence of damage to my own brain. Yet the images are uncannily beautiful, like a map of the stars. How strange and wonderful, to contemplate the inner recesses of my mind. When my father was diagnosed with MS, there was no treatment. The disease causes the body’s immune system to attack the brain, spinal cord and nerves. Dad lived with MS for more than 20 years, the last two years in a wheelchair. Progressive disease confined him to bed, under home hospice care.

Today, more than 15 years after the MS diagnosis, my health is excellent, thanks to expensive drugs developed in the last decade. I am fortunate to have health insurance coverage for the treatments that have kept me symptom-free so far.

I never had to tell my father that I, too, was dealing with MS. He died peacefully at home, less than a week after my diagnosis was confirmed.

Lisa is a retired medical journalist who wrote for International Medical News Group and Reuters Health. She received an MA from the Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University. Lisa is a sexuality educator, a parent, a feminist and a Unitarian Universalist. She lives in the Washington, DC area and is writing a multigenerational memoir about the women in her family.